When most people think of sustainability, they picture solar panels on rooftops, plant-based diets, or recycling bins overflowing with plastic bottles. In healthcare, sustainability is connected to energy-efficient hospitals, low-emission patient transport, and reducing the use of single-use plastics. These efforts matter, but they tell only part of the story.

Equally important is applying the lens of sustainability to science and healthcare research: hidden data, wasted resources, and selective publishing practices have created a completely unsustainable system, one that few outside the research community recognize.

«Science», including clinical and biomedical research, consumes vast resources: funding, infrastructure, time, human energy, and patient participation. Yet, much of this investment is squandered because of a fundamental flaw in how science is communicated. Null, negative, and so-called “orphan” results are routinely concealed.

The consequences are serious: duplication of effort, publication bias, inflated false positives, and slower progress toward treatments and cures. In a world already struggling with resource scarcity and increasing demands on healthcare systems, this inefficiency is unacceptable.

It’s time to look beyond carbon footprints and supply chains, and ask a deeper question: How sustainable is our knowledge ecosystem?

The File Drawer Problem: Lessons learned from a recent Nature Survey

A recent article in Nature, titled “Researchers value null results, but struggle to publish them,” discusses a comprehensive survey conducted by Springer Nature. This survey collected responses from 11,069 researchers across 166 countries, encompassing all major scientific disciplines. The findings highlight the unsustainability of our current publishing practices. The survey outlines several main findings [1]:

- Widespread Recognition of Value: 98% of surveyed researchers recognize the value of sharing null results—outcomes that do not confirm the desired hypothesis.

- Strong Support for Sharing: 85% said it was important to share null or negative results, indicating a substantial community-level agreement about their importance.

- Gap Between Attitude and Action: Despite this recognition, only 68% of researchers who generated null results had shared them in any form, and just 30% had tried to publish them in a journal.

- Barriers to Publication: Among those who hadn’t shared their findings, 69% believed journals wouldn’t accept them, 52% didn’t know where to submit, and others cited costs (19%) or concerns about peer perception (21%).

- Impact on Scientific Record: The lack of published null and negative findings skews the overall scientific “denominator,” leading to an inaccurate version of record and fostering publication bias.

- Benefits of Publishing Null Results: Of those able to publish null results, 39% said it inspired new hypotheses or methodologies; 28% said it prevented wasteful duplication of research efforts by others.

- Systemic and Cultural Barriers: The problem is deeply rooted in both institutional structures and scientific culture, with productivity often assessed by breakthroughs and positive findings, leaving little room for valuing “failure” or negative outcomes.

- Missed Opportunities: Many researchers noted examples where their own work could have taken different directions, or progress could have been quicker, had negative or null results been more accessible—often these were only “buried” in other articles and not clearly flagged or described.

Collectively, these findings reveal a striking paradox: while researchers understand what sustainability in science demands, our systems and culture obstruct its realisation.

Why Negative Results Drive Scientific Progress

Negative results are not failures; they are essential knowledge. They prevent wasted repetition, refine future hypotheses, and clarify what doesn’t work in patients. This accelerates discovery, reduces risks in clinical research, and often sparks entirely new directions.

From a sustainability standpoint, hiding negative outcomes is like discarding half the harvest because some fruit isn’t perfect. A PLoS Medicine study (2022) showed that 30% of trials stop early, often for preventable reasons, and 21% never get published or registered [2]. The result: massive losses of data, money, time, and environmental resources. Incomplete or unpublished results also distort the scientific record. They weaken meta-analyses, bias risk assessments, and slow progress. Notably, industry-funded trials are far more likely to be published than academic ones, leaving much of academia’s contribution unheard.

The takeaway is clear: all trial results, positive or negative, must be openly shared. Otherwise, we risk duplicating work, draining scarce resources, and eroding trust in science. [2]

Orphan Data: The Forgotten Treasure of Science

Beyond unpublished negative results lies and even larger body of overlooked material – “orphan data“. (This is different from orphan drugs, although especially in orphan drug development, more than half trials either never finish or fail to reach the literature [3]. )

So, what exactly is orphan data or orphan results? It includes:

- Confirmatory but non-novel findings

- Single observations or small datasets

- Incremental technical improvements or method tweaks

- Large raw datasets with strong potential for reuse

- Protocol modifications and customizations to name a few.

On their own, these pieces may seem trivial. Collectively, their absence erodes the scaffolding of scientific progress.

In healthcare research, orphan data could, for example:

- Prevent redundant preclinical studies, saving time, resources, and reducing the environmental footprint associated with repeated animal or material use

- Help clinicians refine trial protocols, designing studies that are safer for patients and more efficient in resource use

- Strengthen meta-analyses by integrating all outcomes, building a more reliable evidence base and

- Address the reproducibility crisis, one of the biggest barriers to sustainable biomedical research [4,5].

Orphan data offers unique advantages for making research more efficient, ethical, and sustainable. It saves funding, prevents unnecessary duplication, and protects both patients and researchers—while reinforcing transparency and trust in science.

Ignoring orphan data undermines sustainability at every level. It wastes millions in public and private research funds, consumes the time of scientists and patient volunteers, and weakens public confidence in biomedical research.

In a field where human lives depend on efficiency and honesty, true sustainability means sharing all valid outcomes—not just the “success stories.”

The Publishing Landscape: Where Can Negative and Orphan Results Go?

Encouragingly, the scientific publishing landscape is demonstrating a gradual adaptation. Gradually. An expanding array of publication platforms now specifically welcomes submissions of negative results and orphan data. While still insufficient in number, this represents meaningful progress.

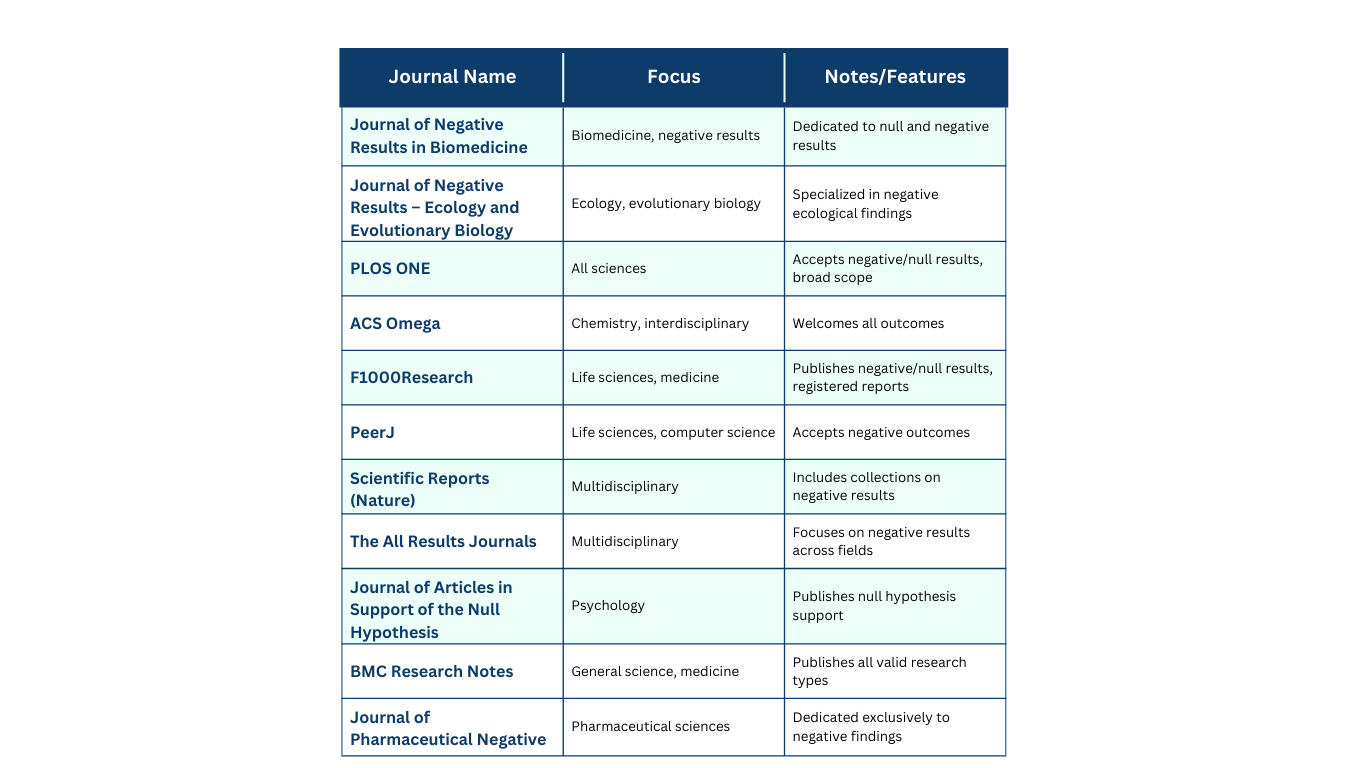

Null or negative results

These journals and platforms explicitly accept negative or null results, making them potential venues for publishing such outcomes and advancing research transparency [6-10].

Orphan data

Orphan data, whether single observations, method tweaks, or large datasets, doesn’t have to remain buried in lab notebooks either.

Scientists now have multiple platforms to share their findings: preprint servers like arXiv, bioRxiv, and medRxiv enable quick sharing at any research stage; micro-publication platforms including BMC Research Notes and Science Matters provide space for standalone observations; methods outlets such as MethodsX and Nature Protocols Exchange welcome protocol modifications; and data journals like Scientific Data conduct peer review of curated datasets. Even megajournals such as PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports accept sound research regardless of novelty. These venues ensure orphan data enriches scientific knowledge rather than gathering dust.

While these publishing options do have their constraints such as article processing charges, incomplete coverage in major databases like PubMed, and preprints lacking peer review – they represent significant progress in addressing science’s sustainability challenges. Together, they provide researchers with diverse and increasingly respected channels to disseminate all research outputs, helping to transform scientific culture and ensure that valuable data, regardless of outcome, advances collective knowledge.

Sustainability demands a Systemic and Cultural Change

Creating new platforms and journals is a step forward, but technical solutions alone cannot solve the sustainability problem in science. At its heart, this is a cultural and systemic issue. To make science truly sustainable, we need a shift in values, incentives, and communication practices across the entire research ecosystem.

- Journals must take the lead. Clear editorial policies should explicitly welcome null, negative, and incremental results. By creating dedicated sections or collections for these outcomes, journals can normalize their value and reduce the stigma that still surrounds publishing “failure.” This is not just about openness—it’s about building a more sustainable scientific record.

- Funders must demand transparency. Public and private funders invest billions into biomedical and clinical research every year. Requiring that all outcomes—positive or negative—are shared as part of grant reporting ensures that this investment is used sustainably, without duplication or unnecessary waste. Transparency saves both money and time, making research more resource-efficient.

- Institutions need to redefine success. Too often, researcher productivity is measured by flashy breakthroughs or publications in high-impact journals. This creates perverse incentives to suppress or “spin” results. A sustainable system must instead value honest contributions to knowledge, reproducibility, and open data sharing. These criteria better reflect the true impact of science on healthcare and society.

- Medical writers and communicators have a pivotal role. They are often the bridge between data and dissemination. By ensuring that negative findings are not buried in appendices, by highlighting orphan data in publications, and by challenging selective storytelling, communicators can make science more transparent and accountable. This not only supports sustainability in research but also strengthens public trust in healthcare evidence. (This is a hard one, but we could try, couldn’t we?)

Sustainability in science will not come from isolated efforts. It requires a coordinated cultural shift, where every stakeholder—journals, funders, institutions, and healthcare communicators—commits to valuing all outcomes. Only then can (bio)medical research become both efficient and sustainable, preserving resources while accelerating meaningful progress.

Why Healthcare Can’t Afford Data Waste

In healthcare research, the cost of hiding data is measured not just in wasted money but in patient lives. Every duplicated trial, every unreported null finding delays the development of treatments. Every orphan dataset left unpublished represents lost potential to improve care.

True sustainability in healthcare science is not about greener conferences (such as taking the train instead of the plane for a 1000 km trip to a conference, or bringing your own cups to events) or eco-friendly hospital supply chains; it is about ensuring that no patient contribution, no dataset, and no outcome is wasted.

From Journals to Smart Platforms: The Next Step for Sustainable Science

Sustainable research means making every result visible, not just the positive ones.

Traditional journals are already overwhelmed and cannot realistically absorb the publication of negative or null data. What science urgently needs is a centralized, AI-powered platform that can automatically process, organize, and categorize research outcomes.

The technology exists, the real barriers are of cultural/political nature: (1) funding bodies rewarding only “success,” (2) universities clinging to prestige metrics, and (3) publishers benefiting from selective visibility. These obstacles are not insurmountable; what’s required is the courage to move beyond outdated models. By embracing AI-driven platforms, we can build a sustainable knowledge ecosystem where no result goes to waste, every trial – positive, negative, or abandoned -advances progress, and trust in medical science is strengthened.

Sustainable science means leaving no result behind. Only then can research truly honor its resources, funders, and above all, its patients.

Learn more about advancing sustainable medical writing with Medtextpert!

References

1 Udesky L. Researchers value null results, but struggle to publish them. Nature. Published online July 22, 2025. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-02312-4.

2 Speich B, Gryaznov D, Busse JW, et al. Nonregistration, discontinuation, and nonpublication of randomized trials: A repeated metaresearch analysis. PLoS Med. 2022;19(4):e1003980. Published 2022 Apr 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003980.

3 Rees CA, Pica N, Monuteaux MC, Bourgeois FT. Noncompletion and nonpublication of trials studying rare diseases: A cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002966. Published 2019 Nov 21. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002966.

4 Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G. Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science. 2014 Sep 19;345(6203):1502–1505. doi:10.1126/science.1255484.

5 Cobey KD, Ebrahimzadeh S, Page MJ, Thibault RT, Nguyen P-Y, Abu-Dalfa F, et al. Biomedical researchers’ perspectives on the reproducibility of research. PLoS Biology. 2024 Nov 5;22(11):e3002870. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3002870.

6 Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results. https://www.pnrjournal.com. Accessed August 22, 2025.

7 Journal of Negative Results in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. https://www.jnr-eeb.org. Accessed August 22, 2025.

8 Enago Academy. Top 10 Journals to Publish Your Negative Results. https://www.enago.com/academy/top-10-journals-publish-negative-results/amp/. Accessed August 22, 2025.

9 Nature. Collection: Negative results in research. https://www.nature.com/collections/gcifjebabg. Accessed August 22, 2025.

10 ZonMw. Journals for Publishing Negative or Neutral Results. https://www.zonmw.nl/sites/zonmw/files/typo3-migrated-files/Journals_for_publishing_negative_or_neutral_results.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2025.

Acknowledgement:

We utilised Generative AI (e.g., Perplexity, ChatGPT) for assistance with structure, content suggestions, and rephrasing. AI-generated text was thoroughly reviewed and edited as needed.

On a personal note:

This article is not intended to be exhaustive but rather to share a personal perspective shaped by my own experience. It was inspired by a recent comment I made on LinkedIn and reflects a concern I have carried for many years: the loss and underuse of valuable research data. Too often, findings remain unpublished, are overlooked for non-scientific reasons, or are duplicated through grant applications on topics already extensively studied. Addressing these issues, I believe, is essential for making science more transparent, efficient, and sustainable.