The purpose of medical writing is not to satisfy or memorialize the author(s), we all know that.

Medical writing is about communicating health and medical-related information to the intended audience clearly and appropriately. Health journalism, medical education, medical promotion of healthcare products, scientific publications and presentations, grant applications and regulatory documents are only a few examples of medical writing.

But when preparing those documents all authors face similar challenges. Arguably, the biggest challenge is how to achieve a clear and accurate message that the reader can understand and relate to.

Although this is relevant within all kinds of writing, we will focus on tips regarding scientific publications; as getting rid of the unnecessary is not only important for authors but medical writers, copyeditors, and reviewers alike. Trying to cover all areas of medical writing would be beyond the scope of a simple blog post.

Eliminate the unnecessary

The phrase “in writing you must kill all your darlings” has been attributed to writer and Nobel prize laureate William Faulkner.

To “kill your darlings” – or eliminate / erase the unnecessary – is one of the most difficult tasks an author has to face. And, believe me, it is one of the most difficult tasks a medical writer or copyeditor has to deal with.

Killing your darlings is all about getting rid of elements or parts of your writing that aren’t important, no matter how much time it took you to create them and how attached you are to them. They must be removed for the sake of the overall message.

But how to do that best and where to start?

1. Start before you begin writing

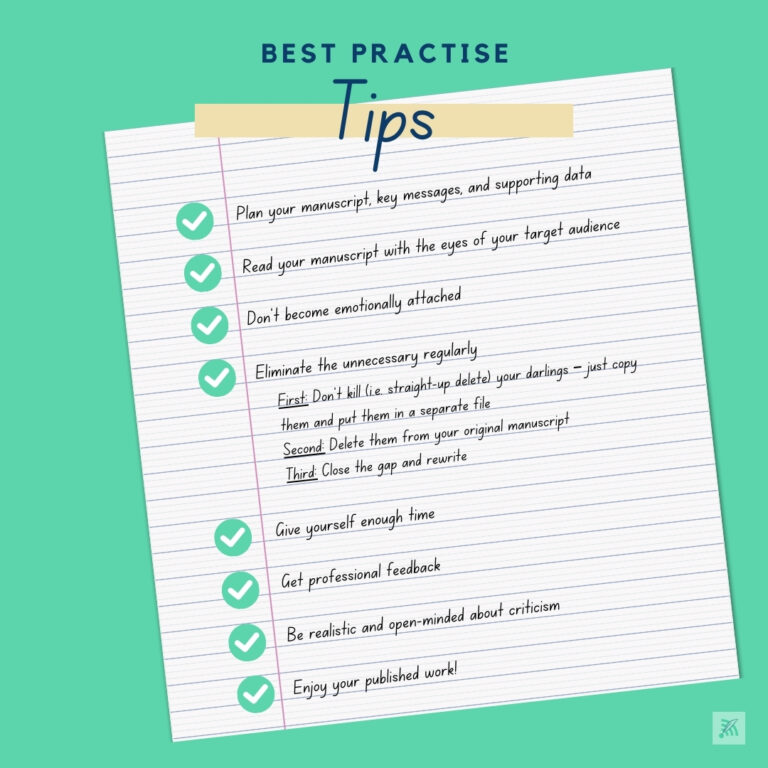

Strategize first. Prepare an outline and agree with your co-authors/team on your key messages, supporting data and ultimate goal – never start without a plan, not even if you are invited to contribute. Read our blog post to publication planning.

When writing in teams, the designated principal author needs to distribute the tasks if possible according to the publication plan or strategy and, of course, guidelines of the designated publication outlet/journal. Good communication comes from communicating often – make sure to be available for questions and exchange – it is a collaborative effort.

Check if it is possible to use systems that allow simultaneous work on a manuscript by using document collaboration tools or cloud workspaces (e.g. google docs).

Remind yourself and your team to put yourself in your readers shoes when writing. Be open to suggestions and critics.

2. Continue when writing

Prepare an outline of the manuscript and start filling in the sections. When selecting supportive data or references, of course depending on the manuscript, it can be helpful to introduce a grading system: important, medium, and supportive.

Read your text aloud. If you trip over a phrase, then your readers will trip over it as well. Clarify, or cut it. If you find that a section of your writing is repetive and doesn’t add any value, then cut it. I know this is very difficult for most, as it is still believed that repetition is key to memory. We know that repetition is just part of the memorization process (RIP – repetition, imagery, pattern), but it would be more beneficial to add a meaningful visualization, instead of crowding your message with repetitive facts.

If you find yourself including superfluous details (which would not have happened with a grading system), that are not significant enough to support your key message, cut them. If you add argumentative details that are facts but don’t advance your thesis, get rid of them.

If permanently removing these parts is too painful, build a new word document into which you can paste them if you change your mind. And that’s that. Works every single time – copy them into a separate file, knowing that they are not lost, and put them aside. It even works with word scraps.

Remember, even though you spent a lot of time writing your draft, if it doesn’t help your readers understand your main message, or provide memorizable value to them, you haven’t achieved your ultimate objective and even risk manuscript rejection.

Don’t overcomplicate everything, break down complex issues into easy to understand parts, complexity does not equate to good or interesting.

Don’t expect to produce a perfect manuscript within only a few “rounds” . Allow and allocate sufficient time for revisions.

3. Don’t stop after the first draft

Writing is as much about rewriting and editing as it is about creating the first draft. Or, to cite Ernest Hemingway: “The only kind of writing is rewriting.”

Once you are done, ask your colleagues to read your first draft and comment. Also explicitly ask them to suggest alterations that could help eliminate unnecessary elements, your darlings.

How to detect those? You recognise it is a darling when someone tripped over a phrase, paragraph, or sentence and said it felt awkward, out of place for them. You can be certain it is one, if you then want to scream something in response and immediately try to explain why you put it there and why you insist on having it there. This is called the “writer-brain” dilemma – the thing a reader slips over – but makes perfect sense to the writer.

My tip: detach yourself emotionally from your writing, your colleague/trial reader has spent time and wants to help you.

If you can’t do it – invest in a professional copyeditor. They are trained and experienced and could save you a lot of extra rounds and frustrations, even later.

4. In the revision process

Authors often experience a range of emotions after receiving a Reconsider with Major Revisions (or, worse, a straight rejection) verdict, including dissatisfaction and, on rare occasions, anger. After all, authors have put in a lot of time and effort to write their manuscript, and it may seem that their efforts have gone unnoticed.

Some authors are understandably concerned that their manuscript has been misinterpreted. Furthermore, in some cases, the author may believe that the manuscript was not given a reasonable chance for a variety of reasons. I assure you – you are all wrong.

First thing – put the correspondence away and allow any emotional response to subside.

Be thankful for the chance to revise your manuscript, even if it means extra experiments, data analysis and re-writing. Keep in mind that revision is where your manuscript goes from a written idea to an article that will interest your readers. And it’s worth the effort.

Be realistic about criticism and keep an open mindset. Answer with a positive attitude and address all suggestions in detail. If it involves killing some of your darlings, know that you have stored them safely away.

Keep in mind that writing a manuscript is not the time-consuming part, but revising and rewriting it. If needed, get professional help.

How to kill someone else’s darlings as a professional medical writer and copyeditor?

Now let’s look at the other side of the medal, the challenge that professional medical writers or copyeditors have to face when it comes to having to kill an author’s, or even worse, a group of author’s darlings.

Bad news first: There is no universal recipe – it is just one of the hats every professional writer has to wear and handle depending on the very situation.

Good news: Medtextpert will share with you how we approach and handle such situations.

Key: When assessing manuscripts, whether it is a first draft or an article in revision we communicate very clearly our “verdict”, no matter how delicate the situation or political.

Of course, there are nights when we could not sleep trying to put together the right argumentation, but with time one gets more experienced in developing strong arguments. It helps to imagine oneself in the shoes of the authors who have spent countless hours researching and writing, to find the right words. Keep in mind that often seasoned professionals are more open to constructive feedback than younger academics. For them especially, don’t forget to provide positive feedback as well.

If there are elements in a manuscript that we think are redundant and clutter the message or need re-writing, we first let them know that they exist. It helps to prepare emotionally to let go. Then we assure them, that editing does not mean taking away from the writers style but taking away the unnecessary to clarify the communication.

We also ask the authors how they would like to receive feedback/changes and accommodate accordingly (e.g. tracked changes in the document, red pen on paper, little video snips to explain why it was done, or even meeting in person to go over the revisions).

In this process, we sometimes offer two drafts, one with structural edits and major cuts, and one with minor touch-ups. Of course that all depends on the task and quality of the draft or manuscript in revision. But in most cases, the authors will only look at the one with the suggested major revisions as they have already started to let go and time is almost always an issue.

When making major revisions, we always take the time to comment/explain why we have removed or rebuilt that section.

Of course, we do not succeed to eliminate all darlings every single time and sometimes darlings walk right back where we removed them from. That’s ok too. Especially when queries from the official reviewers later on confirm what we’d suggested initially. We kind of like it when that happens, as it builds trust in our services and makes it easier to work on the next manuscript together.

Being dead is not the end – it is a start!

Good writing is the result of a meticulous, structured writing and editing process. Courageously editing with the reader and message in mind can transform an unclear rough draft into a compelling manuscript. Keep in mind, reviewers do not like to read poorly written scientific manuscripts, even if the data and methods are good. And readers don’t like to read a cluttered story.

When providing medical writing and editing services, or when wanting to help colleagues – you need to do what is necessary to get the message clear and the paper published regardless of the tears shed along the way. In the end, success counts. Some emotional ups and downs are quickly forgotten and help forge an even stronger professional relationship that starts the day you dared to kill the darlings.

* We would like to thank Stefan Bidula for his valued input and all medical writer colleagues that help medtextpert’s clients kill their darlings on a regular base.