Self-plagiarism is defined as the reuse of one’s words, text, and data, not only in medical or scientific writing. Therefore, textual recycling of previously published own work, if not correctly cited, is considered self-plagiarism.

Many authors have a good understanding of plagiarism but are unaware of self-plagiarism. In their understanding, they are not “stealing” ideas, data, or text from others but instead just reporting their very own work. This becomes particularly apparent when looking at the Materials and Methods section of a research paper. Especially when we think about laboratory protocols, surgical techniques, or standard medical treatment – the materials used and methods applied hardly change, and reporting on them carries the risk of re-using sections of text.

Often self-plagiarism is unintentional. Occasionally, plagiarism can be as well. A forgotten or changed reference or omitted or added text in the revision process can compromise the originally accurate attribution, and trigger a plagiarism checker alarm.

In this blog post, we will look at different forms of self-plagiarism to raise awareness. We will provide tips on how to best avoid self-plagiarism, how best to check for it, list some useful tools and suggest a collection of current, more scientific articles for further reading.

Self-Plagiarism - the basics

Definition of Self-Plagiarism

Re-purposing or re-using original work (text passages included) without proper citation/attribution, in parts or as entirely new work is self-plagiarism, also called auto-plagiarism.

Forms of Self-Plagiarism

There are several forms of self-plagiarism that could be, amongst others, classed as intentional and unintentional.

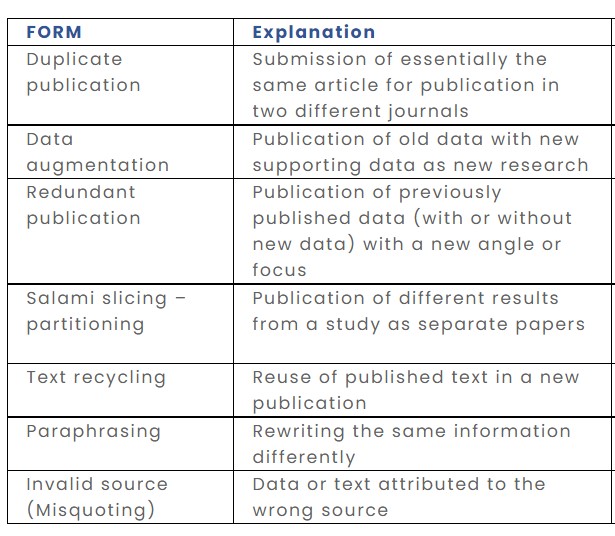

We have created the following table (adapted from Gilliver S, 2012) to summarize the most common forms of self-plagiarism.

FORM | Explanation | Intentional | Unintentional |

Duplicate publication | Submission of essentially the same article for publication in two different journals | x

|

|

Data augmentation | Publication of old data with new supporting data as new research | x

| could be |

Redundant publication | Publication of previously published data (with or without new data) with a new angle or focus | x

| could be |

Salami slicing – partitioning

| Publication of different results from a study as separate papers | x | x |

Text recycling | Reuse of published text in a new publication | x | x |

Paraphrasing | Rewriting the same information differently | x | x |

Invalid source (Misquoting) | Data or text attributed to the wrong source |

| x |

Intentional plagiarism

Reasons for intentional data-recycling (plagiarism) are multi-fold. Reasons for doing such may include the intense academic pressure to publish frequently for reputation, demonstration of competency, scientific attention, or qualification for funding (personal and institution). The article by Rawat S and Meena S (2014) “Publish or perish: Where are we heading?” explains it well. Link to article: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3999612/

Unintentional plagiarism

Unintentional plagiarism occurs when an author does not follow rigorous scholarly citation procedures. Examples can include a forgotten citation, improper citation, or quoting of another author’s or one’s own exact words without marking and referencing simply as the result of inaccurate work.

As plagiarism can be unintentional, sometimes authors, such as busy clinicians, are not even aware that they self-plagiarize. Specifically with text recycling, much uncertainty still exists.

Why is self-plagiarism so wrong?

Self-plagiarism is a clear violation of the ethical standards of scientific research. When recycling old text (or data) as a new contribution, it deceives the audience (Bonnell DA et al, 2012; Broome ME, 2004). It does not only deceive the reader by false claims of originality, but it also challenges the scientific reward system as a whole.

Furthermore, for many publications, the copyright is not held by the authors but by the journal or the publisher. To put it simply, you no longer own your words once they are published. Even when the author has a clear copyright, journal policies might still prohibit text reuse.

Consequences of self-plagiarism are the same as plagiarism and can be far-reaching. They can include rejection or retraction of your work and damage to you and your organization’s professional and academic reputation. Legal repercussions of established plagiarism can be quite serious, as copyright laws are absolute. Plagiarism can also have serious monetary consequences or in some cases be classified a criminal offense. If unlucky, you could end up in jail.

Clear guidelines are needed

To get back to the initial self-plagiarism example involving Materials and Methods sections, many journals now offer guidelines on how to handle previously published Materials and Methods. Some journals specify not to include the previously published text but instead to refer to them (e.g. ‘according to previously published methods (citation)’) or describe standard tests as ‘according to the manufacturer’s instructions‘. Unfortunately, not all journals provide clear policies, and there is no standardization of practices in sight. The absence of clear policy statements on text recycling somehow promotes its likelihood.

There is a set of very useful guidelines on text recycling from the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) offering essential advice to journals.

COPE’s guidance:

“Use of similar or identical phrases in methods sections where there are limited ways to describe a method is not unusual; in fact text recycling may be unavoidable when using a technique that the author has described before and it may actually be of value when a technique that is common to a number of papers is described. Editors should use their discretion and knowledge of the field when deciding how much text overlap is acceptable in the methods section.”...

… “The reuse of a few sentences is clearly different to the verbatim reuse of several paragraphs of text…” (COPE 2016)

There is also a very informative webinar available, issued by COPE in August 2020. Here is the link: Understanding text recycling: COPE August 2020 webinar – YouTube

Despite those guidelines, common practice involves journal editors and reviewers using automated tools to check for plagiarism. These tools apply thresholds to decide if a manuscript is plagiarized. The matching of six or more words in a sequence is usually picked up by the algorithms. For that reason, reused text passages are likely to get flagged and contribute to a higher overall (initial) plagiarism score, hence promoting the immediate rejection of the manuscript. Therefore, do not reuse text passages, including those from the Materials and Methods section. Always make sure to accredit your original source carefully.

Helpful tools that detect and help remove plagiarism

Plagiarism and self-plagiarism can be detected through online tools. It is recommended that you conduct a plagiarism check using one or two of these tools prior to submitting a manuscript to a journal. Reliable online plagiarism checkers include toolssuch as:

- Ithenticate – ithenticate.com

- Grammerly – grammarly.com

- Turnitin – turnitin.com or

- Ouriginal – ouriginal.com.

These sites are widely used by editors and reviewers, above all Ithenticate. As Ithenticate requires a pricey subscription, you should check with your institution before buying credits (100 dollars for 1 manuscript of < 25000 words) or have an agency like medtextpert perform the evaluation for you using their organizational subscription.

Paraphrasing tools can also help you in re-writing flagged sections or sentences. There is a plethora of tools available, both free or with a subscription. Find some listed below:

- Quillbot – https://quillbot.com/

- Spinbot – https://spinbot.com/

- PrePostSEO – https://www.prepostseo.com/paraphrasing-tool

- Paraphrasetool – https://paraphrasetool.com/

Tip: Don’t forget to proofread and check for correct grammar. Paraphrasing tools use machine learning techniques to output paraphrased content, which are not always accurate. Manual checking can help prevent errors and inconsistencies and allows you to adapt changes to the rest of the document.

A look into the literature

There is a substantial body of literature, some very recent, that discusses self-plagiarism. For those who like to dive a little deeper, we have selected some articles for sharing here.

One pillar publication with lots of useful insights and references (and consequently citations) is “The extent and causes of academic text recycling or ‘self-plagiarism’” by Horbach S, Halffmann W, accepted 2017 and published in a special issue of Research Policy in 2019.

The authors of this publication looked at text-recycling in four research areas: biochemistry & molecular biology, economics, history and psychology. Problematic text-recycling was detected in 6.1% of the data sets analyzed- authors affiliated with Dutch universities . Of course, they found varying numbers depending on the research area investigated and found that text-recycling is “more common among productive authors as compared to their less productive colleagues”. (Horbach S and Halffmann W, 2019)

It is published in a special issue of Research Policy (March 2019) which is entirely focused on ‘Academic Misconduct, Misrepresentation and Gaming’ and is a source of other insightful research articles.

Screenshot – Journal Research Policy, Issue March 2019

Another interesting and very recent study done by Pupovac V is looks at the frequency of plagiarism identified by text-matching software in scientific articles (Pupovac V, 2021). Read the abstract below:

Abstract

“The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to determine the frequency of plagiarism in scientific papers estimated from publications that use text-matching software to identify plagiarism. For this purpose, a literature search of 39 bibliographic databases has been conducted and a total of 10,005 articles have been identified. Ten articles met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis and they checked for plagiarism in 6459 already published articles or manuscripts submitted to journals or conferences. All articles assessed plagiarism in a two-step process, first identifying textual similarity based on text-matching software and second, additionally inspecting detected similarity in the human verification process. The result revealed that 18% (95% CI: 12–25%) of articles have instances of plagiarism. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explain the large variance in the results. Following factors were tested: the number of plagiarism criteria implemented during the human verification process, sample size, the country where the study was conducted, the scientific discipline of analyzed papers, and publication status of analyzed papers. Plagiarism rates were higher across studies with a smaller sample size (N < 500) or a larger number of plagiarism criteria used to identify plagiarism (4 or 5 criteria). In conclusion, text-matching software is effective in providing evidence for plagiarism; however, this includes only textually based cases of plagiarism, and the reliability of software results depends on additional human verification.” (Pupovac V, 2021)

Last but not least, we would like to mention a study by Anson IG and Moskovitz C (2020) looking at text recycling in STEM.

Read the abstract below:

Abstract

“Text recycling, sometimes called “self-plagiarism,” is the reuse of material from one’s own existing documents in a newly created work. Over the past decade, text recycling has become an increasingly debated practice in research ethics, especially in science and technology fields. Little is known, however, about researchers’ actual text recycling practices. We report here on a computational analysis of text recycling in published research articles in STEM disciplines. Using a tool we created in R, we analyze a corpus of 400 published articles from 80 federally funded research projects across eight disciplinary clusters. According to our analysis, STEM research groups frequently recycle some material from their previously published articles. On average, papers in our corpus contained about three recycled sentences per article, though a minority of research teams (around 15%) recycled substantially more content. These findings were generally consistent across STEM disciplines. We also find evidence that researchers superficially alter recycled prose much more often than recycling it verbatim. Based on our findings, which suggest that recycling some amount of material is normative in STEM research writing, researchers and editors would benefit from more appropriate and explicit guidance about what constitutes legitimate practice and how authors should report the presence of recycled material.” (Anson IG and Moskovitz C, 2021)

Best practice to avoid Self-Plagiarism

As a summary, we have put together some points that will help you avoid (self-) plagiarism:

- Understand both plagiarism and self-plagiarism and their consequences

- Check journal guidelines

- Always use your own words. If you are a non-native speaker, write in your language and then use a professional translator to translate the document. This also avoids having to look for and recycle text patches that fit your facts.

- Follow rigorous scholarly citation procedures. When creating the structure and especially the body of a manuscript, meticulously add the proper and complete source of the information you want to include.

- Use quotations when re-using text passages as they are and double-check attribution.

- Practice accurate paraphrasing. While writing, use re-phrasing but also change the language, style, and tone of the text. There are good tools out there to help with this.

- Before submitting a manuscript, check it with a plagiarism software, however, do not rely on it.

Last words on “citation adherence”

To answer the question “Can I reuse my own, previously published words in my new manuscript?” the answer is NO.

Do cite and accredit your sources, including your own, completely and carefully according to the motto: ”take your medication regularly and as prescribed”. Doing so does not hurt, and there are guaranteed no side effects.

Plagiarism and self-plagiarism can hurt you and your organization and have serious side effects. Keep in mind that intelligent software utilizes AI to detect all sorts of misconduct, including plagiarism, and it can and will therefore outsmart you.

Medical writers are trained to avoid plagiarism and have utmost interest in avoiding it as their reputation is also at stake.

References:

Anson I, Moskovitz C. Text recycling in STEM: A text-analytic study of recently published research articles. Account Res. 2020;28(6):349-371. doi:10.1080/08989621.2020.1850284

Bonnell DA, Hafner JH, Hersam MC, Kotov NA, Buriak JM, Hammond PT, Javey A, Nordlander P, Parak WJ, Schaak RE, Wee AT, Weiss PS, Rogach AL, Stevens MM, Willson CG. Recycling is not always good: the dangers of self-plagiarism. ACS Nano. 2012 Jan 24;6(1):1-4. doi: 10.1021/nn3000912

Broome ME. Self-plagiarism: oxymoron, fair use, or scientific misconduct? Nurs Outlook. 2004 Nov-Dec;52(6):273-4. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.10.001

Gilliver S. Forgive me for repeating myself: Self-plagiarism in the medical literature. Medical Writing. 2012;21(2):150-153. doi:10.1179/2047480612z.00000000031

Horbach S, Halffman W. The extent and causes of academic text recycling or ‘self-plagiarism’. Res Policy. 2019;48(2):492-502. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.09.004

Pupovac V. The frequency of plagiarism identified by text-matching software in scientific articles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientometrics. 2021;126(11):8981-9003. doi:10.1007/s11192-021-04140-5

Rawat S, Meena S. Publish or perish: Where are we heading? J Res Med Sci. 2014; 19(2):87-9.

Footnote:

As medtextpert is serving academia, we would like to point out that we neither aim for completeness of this article nor take a contentious position by defending misconduct. In mentioning tools and practices to avoid plagiarism we do not intend to provide advice on how to cheat and how to avoid being caught.